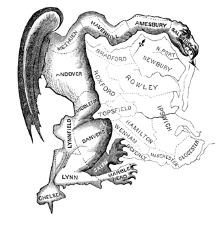

I guess this makes him a full-fledged “Founding Father” of these United States. Nonetheless, his principal legacy is derogatory, since he gave his name to an on-going abuse of democracy, specifically: the egregious configuration of electoral districts. While Governor of Massachusetts, it fell to Gerry to approve that state’s legislative district boundaries in 1811. One such state senate district in the Northeast corner of the state resembled (according to a newspaper at the time) a salamander; and thus the “gerry-mander” was born.

The best solution to the partisan problem has been the recent move in multiple states to establish independent citizens’ commissions to control the boundary-drawing process. We have it here in California and twenty other states. Similar methods are used in many countries around the world. Still, in a highly-partisan and contested environment, there is a lot of energy around what many would call abuses of democracy. It looks like several state legislatures “hi-jacked” their commissions this year to reinsert their political spin. To be sure, this is a bi-partisan issue, i.e., both parties are adept at abusing the process. It’s partially about helping your own team and partially about incumbents’ self-preservation.

As you might guess, I am no fan of letting politicians choose the terms under which they are to be re-elected. But my focus today is on a related practice: the construction of highly-contorted legislative districts to ensure the representation of designated ethnic groups. A recent piece in the Times highlighted this with maps of districts that make Gerry’s salamander look downright orthogonal. Here is the Maryland Third Congressional District.

This approach grew out of a plausible desire to rectify the lack of minority representation in government by designing districts likely to elect a BIPOC.1 The history of voting rights abuses against Blacks in particular is well-documented (and continuing), notwithstanding the Voting Rights legislation of the 1960s and there’s no doubt that gerrymandering has been used extensively to minimize the political power of such groups.

One might argue that “turnabout is fair play” as a justification for contemporary practice; even if it is difficult to justify on its own terms and opens the door to the kind of absurd results illustrated by Maryland. A good idea can easily be taken too far.

My deeper concern, however, is that this approach distorts our politics by insisting on a priority for racial classification. In this, political districting reflects our larger societal fixation on “race” and “national origin.” While there is much for US society to atone for in this regard, especially historically; there is no doubt that using a single frame of classification does a disservice to every person (each of whom is a complex of characteristics and interests). What would Congress or state legislatures look like if districts were drawn on the basis of occupation or age or “class”? In addition, this sort of practice all too easily lends itself to perpetuation and a sense of entitlement. For example, Florida’s current controversy pits the (Republican) Governor against the (Republican-controlled) State Senate, where the latter’s plan is designed to ensure that there is no “retrogression” (i.e. dilution of minority voting strength). Politics makes strange bedfellows, indeed.

The Dems have been wrestling with their version of this challenge in terms of voters of Hispanic heritage. Not only has there been a (problematic) tendency to lump together Cubans, Salvadoreans, Mexicans, and Bolivians; but Dems have too often assumed that as an “oppressed” people, Hispanics would vote Democratic in order to oppose discriminatory policies on immigration and civil rights. However, it appears that these people are, like people everywhere else, interested in social stability, education, jobs, etc., on which the official Democratic Party Line may not be the best on offer.

In a recent posting, I urged consideration of an electoral method—common in many democracies—in which proportional representation was used for at least part of the legislative selection process. This would provide another means of addressing the concern that certain groups were excluded from political power, but would have the advantage that people could pick their own groups and decide for themselves which interests/characteristics were most important to them.

Perhaps it is my legal training that leads me to an underlying belief that good process is a big help if you’re looking for good results. Partisan distortions of democracy not only make it harder to address the people’s actual concerns, but undermine their confidence in the method. “Racially”-based distortions do, too; even if they’re well intentioned. There is a price to be paid, eventually.

The final point to be made returns to poor Mr. Gerry. In fact, he refused to sign the Constitution because he thought the proposed federal government was too powerful and that deferring the recognition of individual rights was dangerous. He signed the “gerrymandering” legislation twenty-four years later even though he thought it too extreme in its partisanship. So much for being able to construct and control one’s legacy.

1 I have to say that I hate this acronym for both semantic and political reasons, but it has gained currency in the last few years. By the same token, I don’t like to use the word “minorities” since (as I have noted in earlier posts) at a global level, it is the “white” folks who are most definitely a minority.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed